I met Oishi-san within a month of moving to Tokyo. At first I thought his name was the Japanese word for “delicious,” which looks basically the same when written in Roman characters. “Delicious,” however, has a short “o” and a long “i”: oishii. My teacher was “Ooishi,” with a long “o” like the city Osaka. The name means “big stone.”

I had gone to the city office the week before to register as a foreign resident, and the clerk had given me a pamphlet for a Japanese class taught by local volunteers. When I ducked through the door of the classroom, Oishi-san was waiting on the tatami mat floor. The other students were mostly young housewives from Vietnam and China; I was the only man. At the time, Oishi was the only male teacher, so everyone thought we’d make a good pair. The match was sealed when we discovered that both of us spoke Indonesian (Oishi worked in Java for several years).

After a year of meeting almost every week, Oishi still greets me with an Indonesian “good morning.” That’s Oishi-san. He was there to teach me Japanese, but he was just as happy to speak any other language, and had no interest in formal language instruction. There were no grammar lessons and no textbooks; instead he preferred to digress on Japanese trade policy, feudal history, and the obscene size of American steaks. Through these conversations, I got fragments of Oishi’s own life story: his childhood in the war, and his years as a salary man in the midst of Japan’s economic boom. After our final class in July, I asked Oishi if we could meet one more time, just to talk about his life and experiences. He agreed.

* * *

Oishi Iwao was born in 1931 on the southern island of Kyushu. At that time Japan was feeling the worldwide economic depression, and his father had moved south to teach in a middle school. The family was not wealthy, even though they were descended from the samurai warrior class. In social rank, this had placed their ancestors clearly above merchants and craftsmen, but it did not guarantee a good income. The Oishi family were low-ranked samurai, which in feudal times meant they had to work part time as school teachers or farm a small plot of land.

In 1934 the Oishi family moved back to Tokyo, just as Japan’s militarists began were expanding their influence in the government. One morning in 1936, Oisihi heard gunshots near his house, an attempted coup by a group of young officers. The coup failed, but actually served to accelerate the rise of militarism. A year later Japan invaded China. Oishi remained in Tokyo until the war began to deteriorate and young children were sent out of the city for safety. By 1944, his school was cancelled entirely and the children instructed to go out and plant rice. Food was scarce then. Japan was cut off from the world by American submarines, and the nation’s farmers had all been sent to the front. Oishi gathered food by day, and listened to the air raids at night. As Oishi tells it, Japan didn’t sleep for one and a half years, just listened to the planes, bombs and guns.

Oishi never seemed troubled by his memories. He leaned back in his chair and laughed as he described his endless school vacation, and used his hands to pantomime planting rice seedlings, or the pumping of anti-aircraft guns. Then with great detail and detachment, he went over the routes taken by the B-29 bombers as they devastated the nation’s great cities: Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Fukuoka.

Oishi’s account of life during wartime was not the oppressive ordeal I had imagined. In fact, he remembers the war as a quiet time, peaceful even. By 1945, all the factories were destroyed, their chimneys shattered. There were no cars, and no gasoline to drive them; electricity worked only a few hours a day. The buildings were leveled and the sky free of smog. Every day, Mt. Fuji was clearly visible in the distance. Today it can only be seen from tall buildings on the few days when the haze moves off the city.

Oishi was relieved when the end came; if the war had dragged on any longer he would have been drafted to fight. Like most Japanese, he listened to the surrender broadcast on August 15, 1945. The emperor’s voice was awkward, his intonation swooping up and down strangely. It was the first time he had addressed his people, and the first time Oishi had heard the voice of his lord. Apparently it was uncomfortable for both of them: Oishi stopped listening and doesn’t remember most of the speech.

The surrender broadcast was one of many unprecedented events to come in the occupation, the beginning of so much change. Oishi was raised in a country mobilized for total war. He didn’t tip his cap and bow to teachers; he said good morning with a military salute, and ended each school day with a “banzai” cheer in praise of the emperor and armed forces. But in the fall of 1945, militarism and blind loyalty were out. Democracy was in, and the American soldiers, reviled enemies just months before, strolled the streets of Tokyo. Oishi said: “If I had been the age I am now, I could not have adjusted, but I was young and my brain could change.” He always described dramatic episodes in this plain fashion, as if shedding fifteen years of indoctrination was as difficult as forgetting the name of a chance acquaintance.

* * *

Oishi was part of the first generation to reach adulthood in modern Japan, and in many ways his story captures the spirit of the time. He soaked in American movies, especially the westerns of John Wayne and Gary Cooper. He was there in 1951 when the San Francisco Seals featuring Joe DiMaggio came to Japan for the first time. They played an exhibition game at Korakuen Stadium, which just a few years earlier had been filled with vegetable plots and anti-aircraft guns. Oishi told me that baseball had actually continued through most of the war years, despite the game’s American roots. The militarists simply demanded that all borrowed English phrases: homu rān, cābu bāru, sutoraiku, be replaced with native Japanese words. Still, the war had taken its toll on Japanese baseball, and the 1951 Tokyo Giants were no match for the Seals. The exhibition game marked another first: the introduction of Coca-Cola to Japan. Oishi tasted a bottle but the drink was too sweet and burned his throat. The second bottle was tolerable and by the third he kind of liked it.

During this time, Oishi made up the schooling he had missed during his endless wartime vacation, and left devastated Tokyo to study metallurgy in the northern city of Sendai. College-educated workers were so scarce in those years that Oishi immediately found work at an engine manufacturing company. One of their biggest clients was actually the American military, which incidentally was also one of the keys to Japan’s rapid economic recovery. Japan’s war industries, only recently dismantled, were remobilized to support the American war effort in Korea. Oishi’s company repaired tank and truck engines, which required him to study their English manuals, as well as the entire system of American manufacturing and quality control.

Many years later, his company provided the same service during the Vietnam War. This time, however, The Detroit auto makers that built the engines were starting to feel the competition from Japanese companies, and weren’t willing to share information. The military was unable or unwilling to mediate an agreement, so Oishi and his team simply took the tanks apart and measured every valve, cylinter, piston and crankshaft. Even with this added labor, his company could supply the replacement parts faster and cheaper than Detroit.

Oishi was the quintessential Japanese salaryman. He came in early and stayed late. He worked over forty years at the same company, starting on the production floor and ending in a top office. He worked through all of Japan’s remarkable recovery from a war-shattered nation to a modern marvel. Oishi finally retired in the late 1990’s, then completed a second bachelor’s degree, and settled into his current routine of reading, biking, teaching, and watching television.

* * *

Some of these stories I have heard a number of times, like the first Coca-Cola, the view of Mt. Fuji, and the plate-sized steak he encountered in his first business trip to Kentucky. Our final session, however, was the first time that he told me of his life from beginning to end. It took a while, and when we finished, he asked if I would like to visit his family’s cemetery plot. The temple that housed the cemetery was nearby, and I had no plans for the day, so we braved the heat and headed for the bus stop.

It is always a little strange when you know a person only in a specific context, and then your relationship suddenly steps into a new setting. I had only ever seen Oishi in the low, wood-paneled rooms of the community center; we had never stood on the street together. Perhaps we looked odd to others as well: a 25-year old foreigner and an 83-year old Japanese man riding the city bus. The discomfort didn’t last, and Oishi proved to be just as informative outside the classroom as he was inside. He pointed out his father’s old neighborhood, which later became a post-war black market, and is now a discount shopping street. A few blocks later we got off on a non-descript street. The temple was set back from the road and surrounded by apartment buildings. It was not a place you would go unless you had a specific reason. This temple, like many others, doubles as a kind of funeral home. There was an air-conditioned entrance area with a water cooler and a basket of rice crackers. We took a seat to cool down. Oishi said it was unusually quiet that day, perhaps because it was just after Obon, a Buddhist festival in which almost all Japanese visit family graves to honor their ancestors.

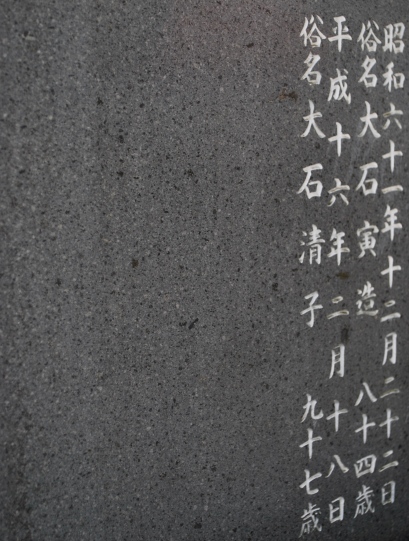

The Oishi family grave is about one meter square and solid stone, with a small tray for holding incense and flowers. On the side are the names of Oishi’s parents, their dates of birth, and death. Oishi tapped the base with his foot to show where a stone slab slides open when the ashes of the dead are placed inside. He said there was still plenty of room, that it was big enough for him to stand in. I know he was just trying to explain the size of the chamber, but I couldn’t shake the image of his body, interred whole, resting here beneath rows of stone alters behind the non-descript temple surrounded by apartment buildings.

The last time I went to the community center for my weekly lesson, a few of the other teachers joined Oishi and I in our side classroom (Oishi’s back has been bothering him so he prefers to sit at a table rather than on the floor in the main classroom). All of the teachers are elderly, and that day I was quizzing them about how Japan has changed in their lifetimes. They all offered their memories, but at one point one of the teachers, I believe it was Fujimoto-san, explained an important distinction. She said that her perspective and Oishi’s were fundamentally different, because he was born before the war, and she was born afterwards. She had never known the old Japan. Oishi, I realized, was the only one who had. He was the only member of the generation that had crossed the divide alive, and lived on to build the modern nation of Japan. That generation is slowly turning to ash, and its memories turning to stories. I am so glad for the chance to hear Oishi’s.